The Golden Mask of King Tutankhamun (King Tut)

The Golden Funerary Mask of King Tutankhamun

Source: Wikipedia Commons, via Tarek Heikal

Title: King Tutankhamun’s Funeral Mask

Artist: Unknown

Date Created: c. 1323 BCE

Medium: gold, obsidian, lapis lazuli, quartzite, glass

Size: 54 cm (height), 39 cm (width)

Art Period: Egyptian New Kingdom

Current Location: Egyptian Museum in Cairo, eventually Grand Egyptian Museum

Quickies:

The iconography from King Tutankhamun’s tomb (like scarabs and lotus flowers) was hugely inspiring to the Art Deco movement.

The Met Museum’s article on Erte and Art Deco influences

The Victoria and Albert Museum article on Art Deco’s global movement

Tutankhamun was born Tutankhaten, or “living image of Aten.” He changed his name when he took the throne.

Prior to Tutankhamun’s discovery, the most famous Pharaohs of Egypt were Cleopatra and Ramses the Great

The international Tutankhamun tour of 1972-1981 was a huge success. In the United States, eight million people waited for hours to be able to enter the exhibit-more than any other art show in U.S. history. The economy of each city the exhibit toured through was boosted significantly through ticket, food, and hotel sales.

King Tutankhamun’s golden funeral mask was found in his tomb by Howard Carter in 1922. The tomb was intact and mostly undisturbed. While it was smaller than other royal tombs, it was filled with treasure. This catapulted a little-known Pharaoh into position as the most famous Egyptian ruler known to man. The opening of the tomb also gave rise to the myth of a “Mummy’s Curse” due to the death of more than twenty people who were connected o the unsealing of the tomb, starting with financier Lord Carnarvon.

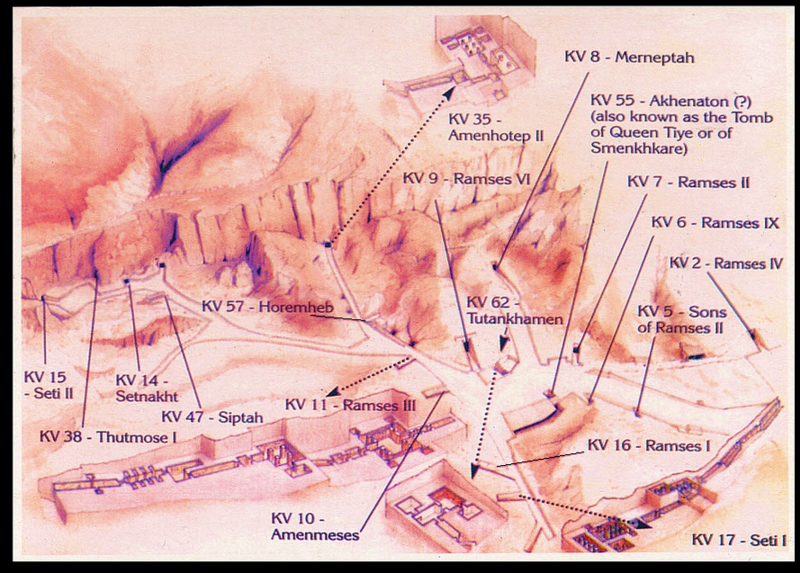

The tomb is named KV62 (Kings’ Valley, tomb 62). The Valley of the Kings is a burial ground for Egyptian Pharaohs. It is located on the west bank of Thebes.

The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter in 1922 was one of the greatest archaeological events of the modern age. The mostly intact tomb was stocked with jewelry, games, home goods, food, wine, the body of the pharaoh and his stunning solid gold funeral mask. Tutankhamun ruled when he was nine years of age. He died young, creating a power vacuum. His tomb’s discovery propelled him to international stardom, even though his short reign was less impressive than many of his ancestors.

King Tutankhamun’s tomb gives a distinctive insight into royal Egyptian tombs, royal mummification practices, and domesticity of the royal court. His tomb is not the only royal tomb that was found intact, but it is the richest. For instance, in 1995 a burial complex near Thebes was discovered, it is thought to be the resting place of many of Ramses II’s children.

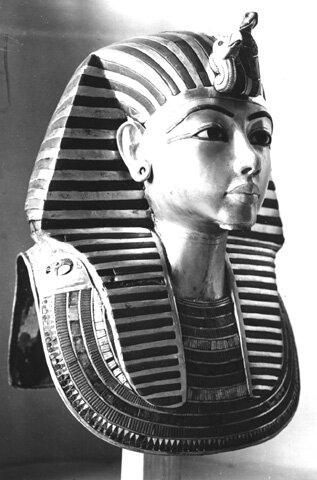

His burial mask is the most famous object from his tomb. It is internationally recognizable. Egypt has sent it on international tours, cementing the face of King Tutankhamun in memory. It is solid gold, inset with precious jewels, and features an artistic expression of a wistful young man.

Life of King Tutankhamun

Amarna

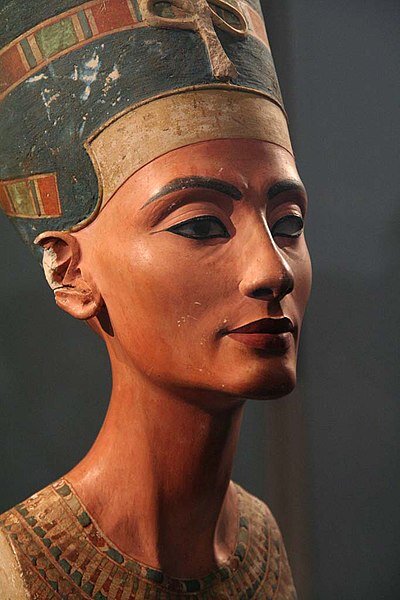

Tutankhamun’s father was Akhenaten/Amenhotep IV, who was married to the famously beautiful Nefertiti. Akhenaton was known as the “heretic” pharaoh because he changed the Egyptian religion and his name. Dissatisfied with the power of the priests, Akhenaten decided that the nation should worship one deity (monotheism) which was at odds with the old religions of many golds (polytheism).

Akhenaton moved the royal court from Thebes to a new city, Amarna. He changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten. The priests of the god Amun had been gaining power and wealth since Akhenaten’s father (Amenhotep III) was Pharaoh. To combat this, Akhenaten outlawed the old polytheistic religion and proclaimed himself the living incarnation of the deity Aten, a sun god. This paved the way for him to usurp the power and wealth of the priests.

Tutankhamun was born in the eleventh year of his father’s reign (1341 BCE). He was originally named Tutankhaten, or “living image of Aten”. His mother was not Nefertiti but one of the Pharaoh’s lesser wives, it was once thought Kiya. DNA testing has discovered that Tutankhamun’s mother is most likely the mummy named “The Younger Lady.” It is unsure who the mummy is. Tutankhamun was betrothed to his half-sister, Ankhesenpaaten (which means, “her life is of Aten”) when they were both children. She was the third eldest of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s daughters.

Near the end of Akhenaten’s rule, he appointed Neferneferuaten as co-ruler. This might have been Nefertiti, as she seemed to have elevated power that can be seen in Amarna art, but it is not certain. After Akehnaten’s death, Neferneferuaten ruled for three additional years before a figure named Smenkhkara assumed the throne. Smenkhkara might have been Nefertiti again or a male relative of Akhenaten.

Ascension to the Throne

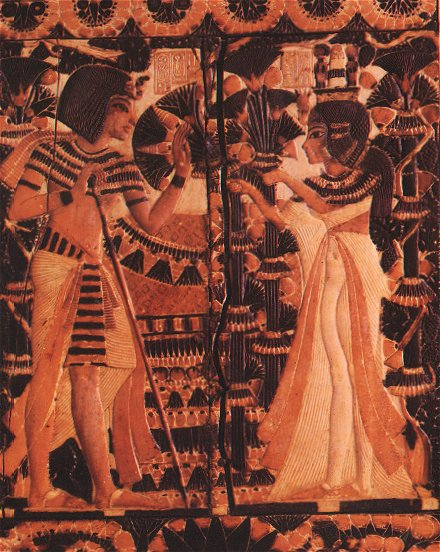

Tutankhamun ascended to the throne around the age of eight or nine. He was joined by his wife, Ankhesenpaaten. She was most likely older than him, perhaps around thirteen.

With the aid of advisors Ay and Horemheb, Tutankhamun returned to the old religion. He changed his name to Tutankhamun and moved the royal court back to Thebes. His wife changed her name to Ankhsenamun. Tutankhamun also began a program to build and restore the temples. While this restored power and wealth to the priests, it positively impacted the people of Egypt who had been in turmoil with Akhenaten’s changes.

During his reign, Tutankhamun leaned heavily on Ay and Horemheb. Ay was an elderly official, of long standing with the royal family. Horemheb was the general of the armies.

Tutankhamun’s legacy (other than being discovered in the 1920s) was the construction of the Temple of Karnak, a memorial temple in Thebes, and reliefs on the Colonnade of the Temple of Luxor.

Death

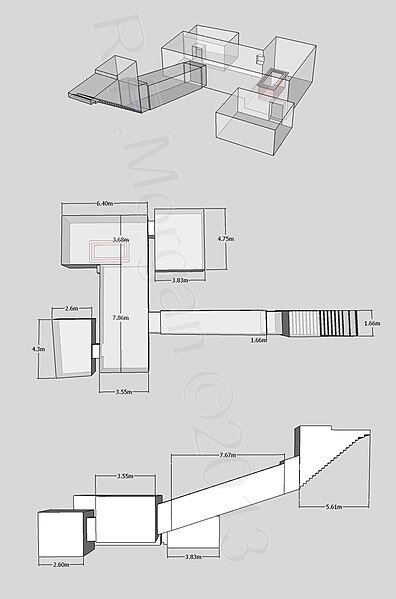

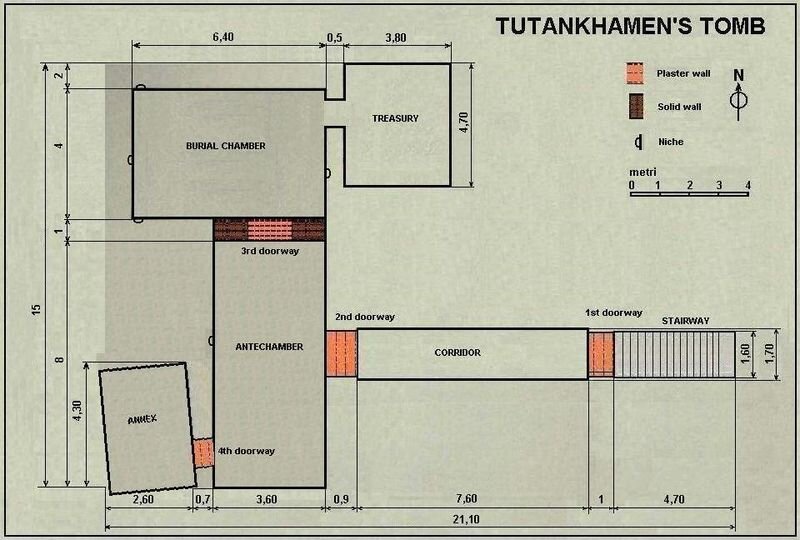

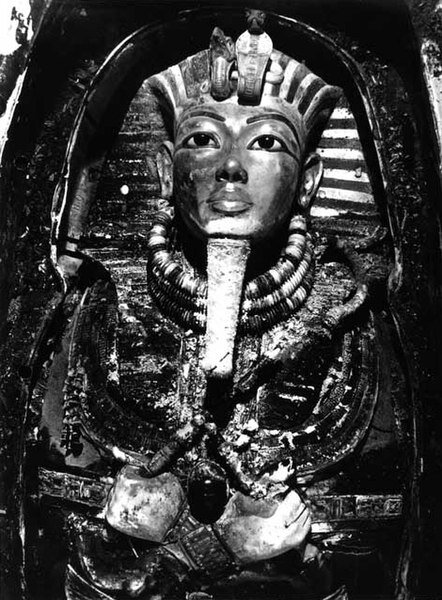

Tutankhamun ruled for close to ten years, dying at the age of 17-19. Tutankhamun was buried in a smaller tomb, most likely converted for this use. His mummification was elaborate, befitting that of a Pharaoh. His eternal organs were removed and placed in canopic jars. More than one hundred amulets were wrapped in his mummy. His mummified body was placed in a series of nesting coffins with his solid gold funerary mask placed on top.

Egyptian scientists have run several tests on Tutankhamun’s body and discovered that he had a broken right leg and malaria at the time of his death. Tutankhamun also had a curved spine, a club foot, and other medical issues caused by the common incestuous relations in his family tree.

His death caused an issue as the only children he had with Ankhsenamun were stillborn. Most likely, Egypt was engaged in war with the Hittite Kingdom. This meant Horemheb was in battle. This left Ay to supervise Tutankhamun’s tomb work and death rites. Ay then assumed power and crowned himself Pharaoh. To legitimize his rule, Ay needed to marry Ankhsenamun. In a daring risk, she wrote the Hittite King Suppiluliuma I and asked for one of his sons to marry. This was unheard of as Egyptian princesses did not marry foreign men. King Suppiluliuma sent his son Zananza, but Zananza was killed (perhaps by Horemheb’s efforts) before reaching Ankhsenamun. Ankhsenamun disappeared from the historical records, it is not known for certain if she married Ay. Ay ruled for three years and died without an heir.

Horemheb returned from war and took the throne. He had the same issue as Ay-legitimacy. To circumvent this, he claimed to be chosen by the god Horus to restore Egypt. To further legitimize himself and draw closer to the priests, he destroyed the public records and monuments erected by Akhenaten as well as records of Tutankhamun. Horemheb ruled for about thirty years.

Discovery by Carter

Tutankhamun’s tomb was virtually intact when Howard Carter first discovered it. It had been broken into during Ay’s reign and resealed. Ironically, the tomb was partially saved from grave robbers because Horemheb had erased Tutankhamun’s name from the official records. This ended up saving Tutankhamun’s name and tomb for the modern age. The entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb was also further buried with the construction of Ramses VI (buried about two hundred years after Tutankhamun).

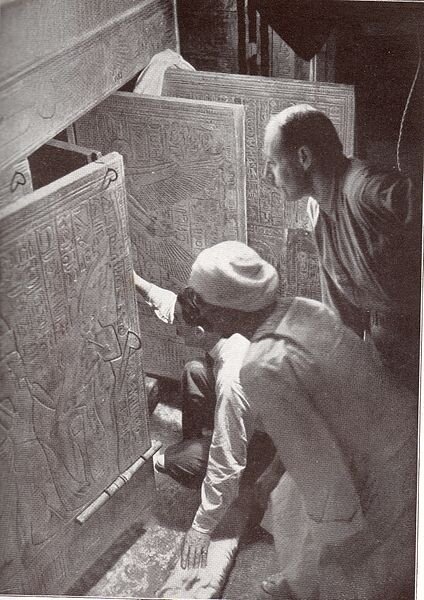

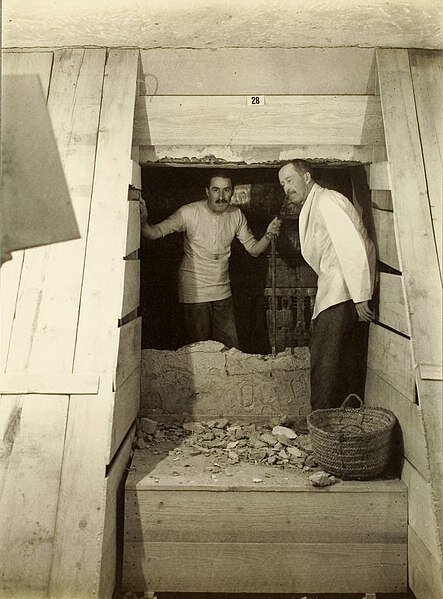

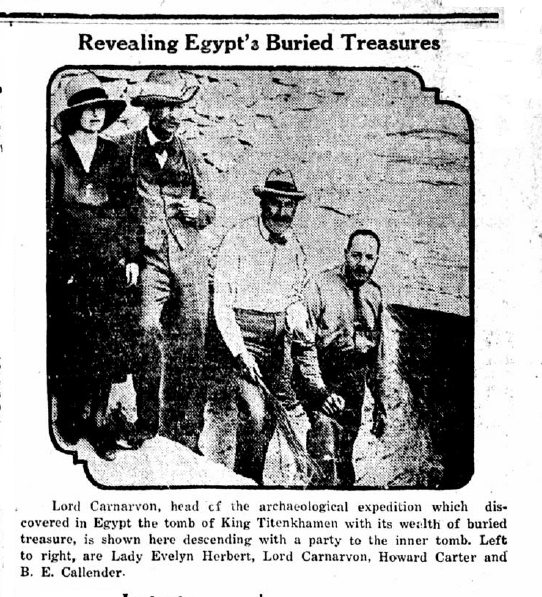

Howard Carter’s archaeological digs were sponsored by the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, George Herbert, but his funding was running out. Lord Carnarvon was only going to finance until the end of 1922. Carter was digging in the Theban Necropolis in the Valley of the Kings. On 4 November 1922 CE, Carter discovered the entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb-the twelve steps that led to the sealed door. After waiting for Carnarvon and his daughter to travel from England, the tomb was opened in 1923.

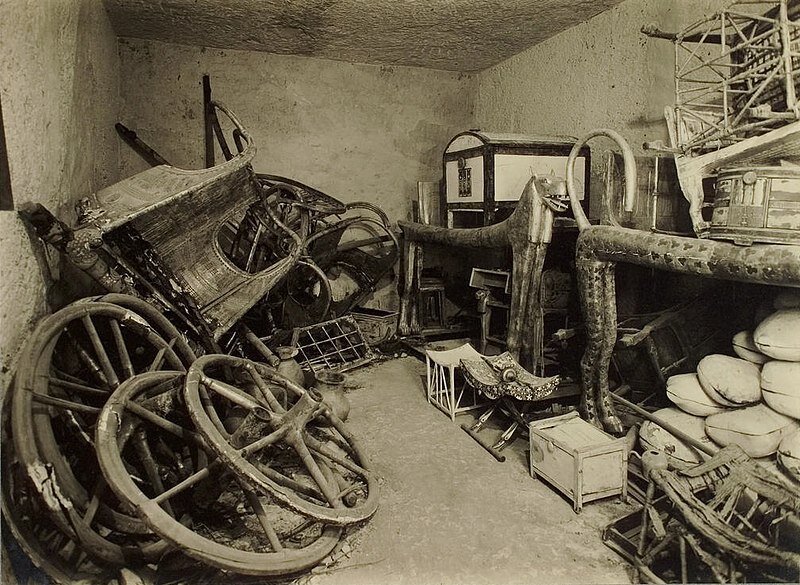

Carter spent the next ten years cataloguing the contents of the tomb. The sarcophagus wasn’t opened until October 1925. Carter wrote of opening the innermost coffin, “The penultimate scene was disclosed—a very neatly wrapped mummy of the young king, with golden mask of sad but tranquil expression…the mask has fallen slightly back, thus its gaze it straight up to the heavens.”

The Metropolitan Museum in New York City sent a photographer named Harry Burton to document the excavation and discoveries that Carter made. Burton took over 1,400 photographs which helped to raise excitement around the world. With the press and radio creating an environment for instant news, the discovery started Egyptomania worldwide.

The “Mummy’s Curse” associated with the tomb is because of a mistranslation of the door’s seal and the multiple deaths of people associated with the tomb opening. The translated sentence is from the door of the treasury room. It was mistranslated and thought to have said, “I will kill all of those who cross this threshold into the sacred precincts of the royal king who lives forever.” More modern translations suggest that is reads, “I am the one who prevents the sand from blocking the secret chamber.” The “I” is the spirit that keeps the door closed. Few months after the tomb’s opening, Lord Carnarvon, died. The international press kept tabs and conflated the deaths of anyone tangentially related to the tomb to the curse. In fact, Lord Carnarvon died in 1923 due to blood poisoning due to an infected mosquito bite. Howard Carter lived until the age of 64; as the primary trespasser of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, his prolonged life would prove any curse false.

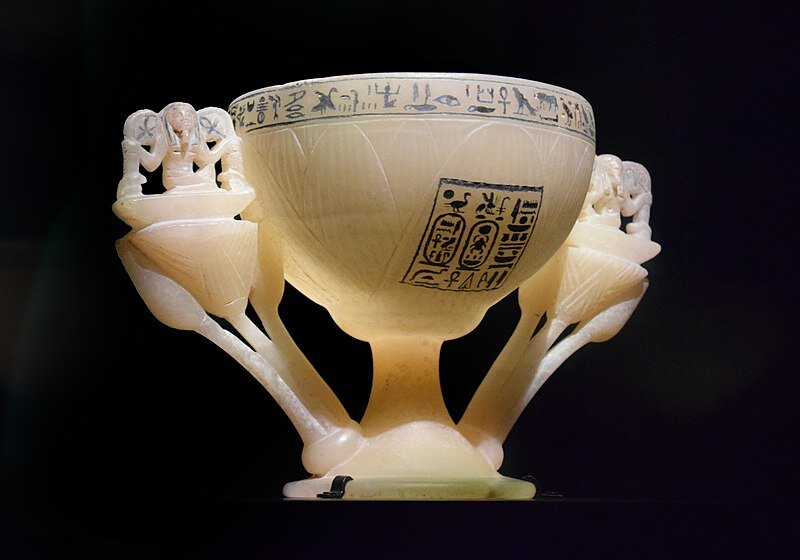

Contents from Tutankhamun’s Tomb

There were 5, 398 items inside Tutankhamun’s tomb. Many were solid gold and bejeweled. There were 143 pieces of gold jewelry in the mummy linens alone. The solid gold funerary mask is likely the most famous item from the tomb, but Tutankhamun’s gold throne and solid gold coffin are also renowned.

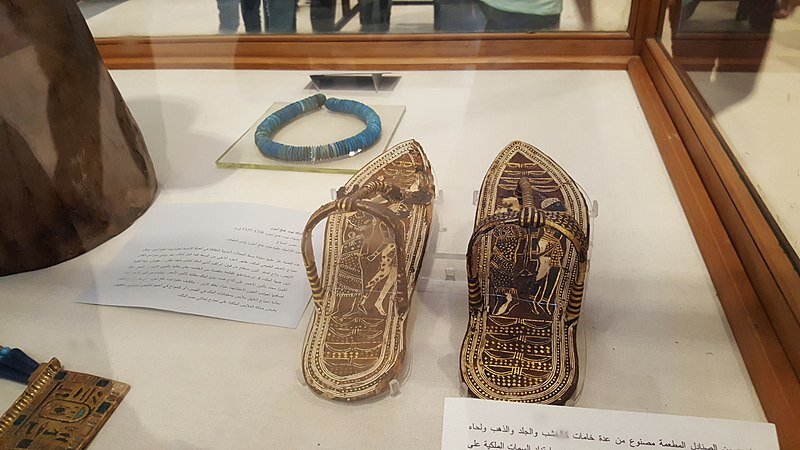

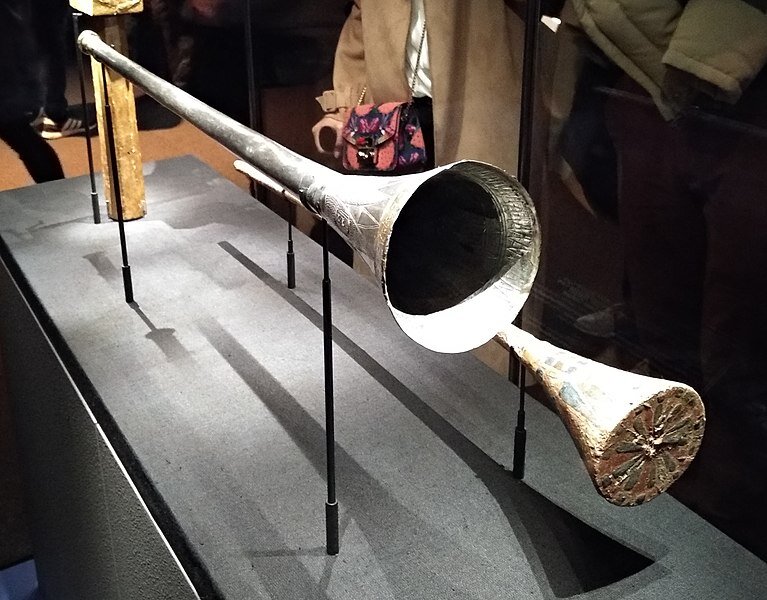

Some of the items in the tomb were household items, like Tutankhamun’s clothes, now in delicate condition. Tutankhamun also had sandals, cosmetics, and jewelry to adorn him in his afterlife. Jars of beer, wine, and oils were packed tight amongst baskets of fruit and grains. Furniture like beds, tables, and chairs are heavily decorated and stored on top of one another. Board games, toys, and musical instruments were also provided for the Pharaoh’s entertainment.

A shield with cheetah skin, chariot wheels, chariots, and other weapons showcase the prowess of not only the Pharaoh but the Egyptian state. Also, statues of Egyptian gods are placed around the tomb to protect the Pharaoh. Other statues of previous pharaohs are meant to showcase the familial tie Tutankhamun had to previous Kings.

Other items point to Tutankhamun’s medical issues. More than one hundred canes and walking sticks were found in the tomb. Tutankhamun suffered from a degenerative bone disease in one foot, causing him pain when it swelled from inflammation. The mummies from his two stillborn daughters were also placed in his tomb to be with him in his afterlife.

Tutankhamun’s mummy was placed in the innermost of four sarcophagi. The final coffin was gold and sealed with resin. The resin was also on the mummy linens, requiring careful handling by Howard Carter.

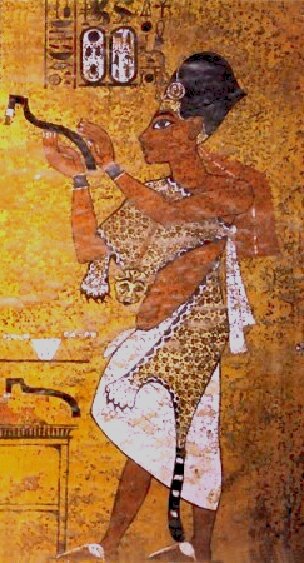

Only the walls of the burial chamber have any decoration. Other royal tombs have decorations in many (if not all) rooms. The one room is beautifully decorated, with one scene from a funerary text (Amduat), scenes from Tutankhamun’s funeral, and Tutankhamun with Egyptian gods.

King Tutankhamun’s Funerary Mask

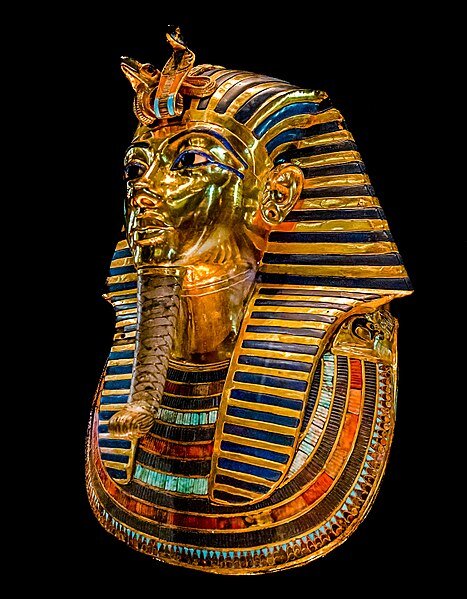

The funerary mask might be one of the most famous artistic items in all of Egypt’s history. Since the discovery, it’s been the international emblem of Egyptian cognizance. It’s pure gold, composed of two sheets that were hammered together after being heated. The final layer of gold has a high silver content, which gives the mask extra radiance. The mask weighs in at 22 ½ pounds (11 kilograms). It is 21 inches tall (54 centimeters). The mask has semi-precious stones, glass, and faience (glazed ceramic) that are used for decoration. The eyes on the mask are made from white quartz and black obsidian, with red pigment in the corners. Blue lapis lazuli forms the lines of kohl that Tutankhamun would have worn in life; it also creates the lines for his eyebrows and eyelids. The rest of the decoration on the mask emphasized his role as Pharaoh.

The mask shows Tutankhamun wearing the nemes headdress, worn by Pharaoh’s since the Old Kingdom, decorated with stripes of gold and blue paste. The nemes is topped by symbols of Egypt, the cobra and vulture (the goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet). They’re encrusted with turquoise, carnelian, obsidian, and lapis lazuli. The bottom of his mask forms a collar decorated with lapis lazuli, quartz, green feldspar, amazonite, and colored glass cloisonné. Golden falcon heads, ornamented with obsidian and glass, brace his shoulder. A triple-string beaded necklace was laid across the mask’s neck but is not shown on the mask in the museum case.

The point of the funerary mask was not only to protect the mummy’s face and head but to reunite the soul (“ba”) to the body after its wanderings. Identifications are used to help the soul recognize the mummy. Two of the most obvious are the symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt, symbolizing Tutankhamun’s authority over both lands. The vulture, or Nekhbet, is the symbol of Upper Egypt. The cobra, of Wadjet, is the symbol of Lower Egypt. The facial features are thought to be an idealized version of Tutankhamun. While Osiris (the Egyptian god of the afterlife) was the Pharaonic ideal, the features are similar to other statues of Tutankhamun. The mask alludes to artistic trends of Akhenaten’s Amarna period. Elongated features, with full lips and a thin nose, might be true to form but also follow the Amarna style. The Amarna style is naturalistic and exaggerated, like the Mannerist style that followed the Italian Renaissance.

The ears are pierced, perhaps signifying that the mask was meant for a woman but converted to Tutankhamun upon his death. Pierced ears were a feature reserved for Egyptian Queens and young children. When found by Howard Carter, the holes in the lobes were covered with disks of gold foil.

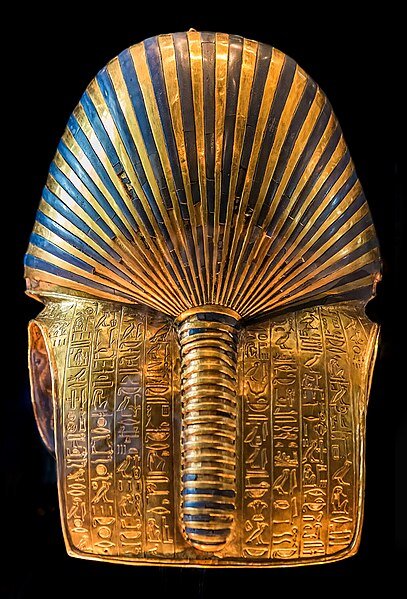

The back of the mask has a “spell” engraved from chapter 151 B of The Book of the Dead. This spell goes back five hundred years before Tutankhamun, to mummies from the Middle Kingdom. The spell protects the body of Tutankhamun as he moves to the afterlife. The spell says:

“Your right eye is the night bark [of the sun god], your left eye is the day bark, your eyebrows are [those of] the Ennead of the Gods, your forehead is [that of] Anubis, the nape of your neck is [that of] Horus, your locks of hair are [those of] Ptah-Sokar. [You are] in front of the Osiris [Tutankhamun]. He sees thanks to you, you guide him to the goodly ways, you smite for him the confederates of Seth so that he may overthrow your enemies before the Ennead of the Gods in the great Castle of the Prince, which is in Heliopolis…the Osiris, the King of Upper Egypt Nebheperure (Tutankhamun’s throne name), deceased, given life by Ra. ”

Tutankhamun would have worn a false beard in life; his funerary mask also has one. It’s a gold beard decorated with cloisonné in a herringbone pattern. The beard of the mask broke in August 2014 when employees were fixing display lights. It was at first glued back on using an epoxy, but it dried off center and left a thick band of visible epoxy. Conservation was led by restoration expert Christian Eckmann, from the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Archaeological Research Institute in Mainz. His team took the beard off by heating the glue and using wooden rods and learned that ancient Egyptians used beeswax and a pin to attach the beard. The mask was reattached after a 3D scan and more research into the original attachment process. It was originally attached using a small pin as the beard was hollow but placed over a metal cylinder sleeve that was attached. While the break was at first considered a disaster, it has allowed scientists to study the beard in detail. Accidents in museums do happen and they do allow research and conservation to the objects. This isn’t the first time the beard has been unattached. When it was discovered in 1925, the gold beard was mostly separated and Howard Carter removed it. It was reattached in 1946 for the first time.

The Importance of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb

As the tomb was found intact, a rarity, giving archaeologists keen understanding of ancient Egyptian burial practices and civilization. Most of our knowledge on Pharaonic burial practices and funerary regalia comes from Tutankhamun’s tomb. While the sumptuous riches are packed tightly, its noticeable that the actual tomb is very small for a Pharaoh. It is only four rooms. It might have been unfinished or repurposed after the surprise death of Tutankhamun.

What also helped the fame of Tutankhamun was the interest that the print media gave to the discovery. In the 1920s, photos that Harry Burton took of the excavation ran in newsprint worldwide. The newspapers coined the name “King Tut” and the phenomenon quickly followed. The many photos of the gold funerary mask, with its haunting face, captured imaginations and gave the mask icon status. The attention gave a minor Pharaoh place at the front of all others.

Egyptian Museum

King Tutankhamun’s gold funerary mask has been on display at the Egyptian Museum since the 1920s. The Egyptian Museum is in downtown Cairo and has limitations on display space, meaning only one third of King Tutankhamun’s artifacts are on display at most.

The Egyptian government has been building a new modern museum called the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM). It’s located two kilometers/over one mile from the famed Giza pyramids, west of Cairo. When it opens, the GEM will be the largest museum ( around 120 acres) in the world that is dedicated to a single civilization. The Egyptian Museum will undergo a renovation once the GEM opens.

Eventually, all the artifacts from King Tutankhamun’s tomb will be moved to the new museum. The final grouping, including the burial mask, will be moved before the grand opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM). They will most likely be moved in a procession like the Pharaoh’s Golden Parade. The Pharaoh’s Golden Parade was the celebrated transfer of twenty-two royal mummies between the Egyptian Museum and National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

King Tutankhamun’s tomb had over five thousand artifacts and all will be on display at GEM. The display will occupy two halls of about 7000 square meters/7500 square feet. The idea is to arrange the artifacts to look like they did when Howard Carter opened King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

Articles:

Information and Documents from Howard Carter’s excavation, currently housed at the Griffith Institute at Oxford University.

Tyson, Peter. “Undiscovered Tombs.” PBS.

The New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art sent a photographer named Harry Burton to Howard Carter’s excavation. He took around 2,800 glass negatives. Some of these black and white negatives have been colorized by Jordan Lloyd (rom Dynamichrome). They can be seen in the article from ArtNet, titled “See Glorious Color Photos of King Tut’s Tomb.”

An in-depth article (Tutankhamun’s Funeral) about the Egyptian mummification process from The Met Museum.

The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities has placed a virtual tour of King Tutankhamun’s exhibit online

Location

Lost Treasures of Egypt: Tutankhamun’s Treasures from National Geographic

King Tut from PBS

The Metropolitan Museum in New York City’s lecture series covered King Tutankhamun’s Golden Funeral Mask.

Works Cited:

Burzacott, Jeff. “The First Hi-Res Photo of Tutankhamun’s Restored Golden Mask.” Nile Magazine. 2015.

Cummins, Elizabeth. “Tutankhamun’s tomb (innermost coffin and death mask.” Khan Academy.

Cummins, Elizabeth. “Tutankhamun’s Tomb (innermost coffin and death mask.” Smart History. 2015.

Diab, Sima and Louis Cheslaw. “Everything we know about the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo”. Conde Nast Traveler. 2019/2020.

Donovan, John. “How King Tut Became a Pharaonic Rock Star Only After Death.” How Stuff Works. 2020.

Dorman, Peter F. “Tutankhamun.” Britannica.

Gallup, Alison, Gerhard Gruitrooy, and Elizabeth M. Weisberg. Great Paintings of the Western World. Art Resource. 1998.

Grand Egyptian Museum/Giza Museum.

Hamilton, Jon. “Frail and sickly, King Tut suffered through life.” NPR. 2010.

Hastings, Rob. “Tutankhamun has a new home worth waiting for inside Cairo’s delayed Grand Egyptian Museum.” INews. 2020.

Hosny, Hagar. “Egypt plans another royal parade, this time for King Tut’s gold mask.” Al-Monitor. 2021.

Jones, Jonathan. “Funerary Mask of Tutankhamen (c. 1323 BC).” The Guardian. 2002.

Kamp, David. “The King of New York.” Vanity Fair. 2013

Keyes, Allison. “For the first time, all 5,000 objects found inside King Tut’s tomb will be displayed together.” Smithsonian Magazine. 2016.

Kleiner, Fred S. and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: 12th Edition. Thomson Wadsworth. 2005.

Marie, Mustafa. “Anani: Tutankhamun’s mask will be transferred to GEM in a way that befits the most famous artifact in the world.” Egypt Today. 2020.

Mark, Joshua. “Tutankhamun.” World History. 2014.

Matthews, Roy T. and F. DeWitt Platt. The Western Humanities. McGraw Hill. 2004.

McDonald, Diana. “The Mask of Tutankhamun.” The Great Courses. 2017.

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History: Revised Second Edition: Volume I. Pearson Prentice Hall. 2005.

Strickland, Carol. The Annotated Mona Lisa: A Crash Course in Art History From Prehistoric to Post-Modern. Andrews and McMeel. 1992.

Tyson, Peter. “Undiscovered Tombs.” PBS.

Walsh, Colleen. “How Tut Became Tut.” The Harvard Gazette. 2018.

White, Mark. “How the discovery of King Tut’s tomb revolutionized our knowledge of Ancient Egypt.” SBS. 2016.

Vermillion, Stephanie. “A ‘secret’ tour inside the long-awaited Grant Egyptian Museum.” CNN. 2019.

Unknown. “Egypt: King Tut’s Golden Mask Restored, Back On Display in the Egyptian Museum.” Aswat Masriya/All Africa. 2015.

Unknown. “Facts on Tutankhamun’s Tomb.” Phys. 2016.

Unknown. “German expert restores King Tut mask after botched glue job.” DW.

Unknown. “Mask of Tutankhamun.” Wikipedia

Unknown. “The Gold Mask of Tutankhamun.” Global Egyptian Museum.

Unknown. “Tomb of Tutankhamun.” Egypt Monuments.

Unknown. “Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BC).” BBC.

Unknown. “Tutankhamun’s Death Mask.” King Tut Exhibition.

Unknown. “Tut Exhibit – King Tutankhamun Exhibit, Collection: Basic Funeral Equipment – Gold Death Mask of Tutankhamun.” Tour Egypt.

Unknown. “Tutankhamun’s gold mask back on display in Egypt after beard restoration.” Agency France-Presse/The Guardian. 2015.

Unknown. “What the world might discover from the King Tut mask restoration.” DW.

Zorich, Zach. “5 Unsolved Mysteries of King Tut’s Tomb.” Scientific America. 2016.